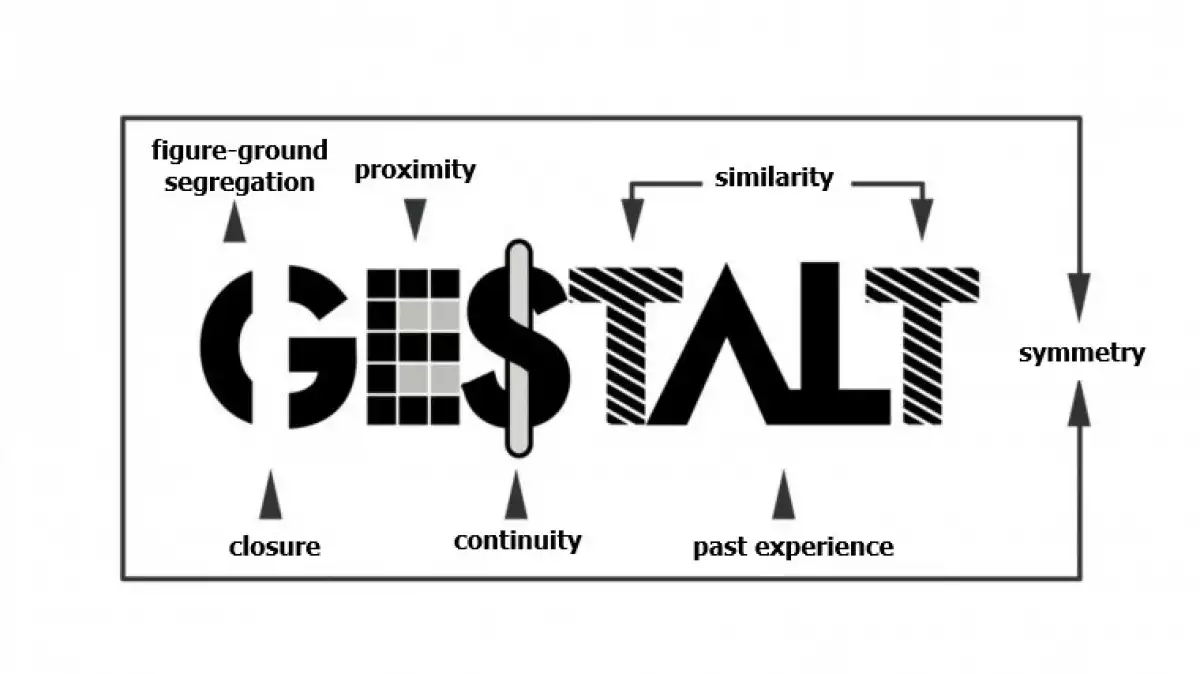

Gestalt psychology explains human perception (using different laws) and is also a branch of psychotherapy. Max Wertheimer is the founder of Gestalt psychology, while Fritz Perls established the Gestalt therapy practice. In the following article, we take a closer look at Gestalt psychology's theory and its 6 principles or laws on perception: the laws of proximity, closure, continuity, similarity, pragnanz, and figure ground relationship. Besides, we explain the therapy that shares its name.

Gestalt psychology: the principles of perception

The word "Gestalt" is German for "shape"; which is why this German school of psychology that studies human perception bears this name. At the same time, the word perception means knowledge or a feeling inside that occurs when we receive certain information via the senses. This has to do with the shapes or mental structures that we perceive our external reality through.

To go into further detail, Gestalt psychology studies the organization of these shapes or mental structures that lead to the way that we perceive things. Perception psychology is a school of thought created in the early 20th century by German psychologists Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Kohler, and Kurt Kofka.

Among other things, these founding fathers suggested that perception is the first step that the mind takes when a person experiences something; an idea that went against everything that the psychophysiology field stood for at that point in time, when people believed that the sensorial experience came first, followed by mental activity.

According to these creators, mental tasks such as learning, thought, and memory, would be impossible without perception. And to explain how the mind configures the information that we receive, these psychologists proposed a series of principles know as the Gestalt laws.

Related: Enneagram Types: Your Personality Based On This Test

The 6 main Gestalt principles

Gestalt psychology suggests that contrary to what one might think, perception occurs in the form of partial registration of the phenomena occurring around us. In other words, when we perceive, we aren't capable of registering everything exactly as it's happening in reality; instead, we extract and select the information that is most relevant to us.

What this means is that perception isn't a passive activity: we organize events in the external world through judgments and categories that, at the same time, help us to relate them to valuable qualities so that we can represent them.

This explains why sometimes we perceive things in a distorted way or with added information, in an attempt to formulate a mental picture of an object that we observe (like what happens with 'optical illusions'). So, which Gestalt principles explain all of this? Read below to find out.

1. Law of proximity

The law of proximity says that we categorize information from the outside world based on the spatial distribution of the objects that we observe. In other words, we tend to create a mental picture of these objects depending on the space between them: we perceive objects that are close together as a single entity. For example, if we see six rows of dots distributed into three columns (of two rows) which are separated, we would define them in the same way as if we were seeing them all together.

2. Law of closure

The law of closure is closely related to the law of pragnanz. In large part, it says that we prioritize the information that helps us to create outlines or edges around shapes. This is different from stimuli that don't generate any image or mental possibility for closure. For example, if we see lines that form a triangle, but this potential triangle is missing a vertex, we would still view this shape as triangular.

Related: Types Of Triangles By Sides And Angles

3. Law of continuity

The laws of closure, pragnanz, and proximity are closely related to the law of continuity. This principle explains that we tend to perceive details that are close together as continuous when in reality they are separated or interrupted.

For example, there is the tendency to complete or continue patterns mentally, even if they are incomplete, just because they continuously present themselves (they repeat so frequently that it removes the feeling of interruption).

4. Law of similarity

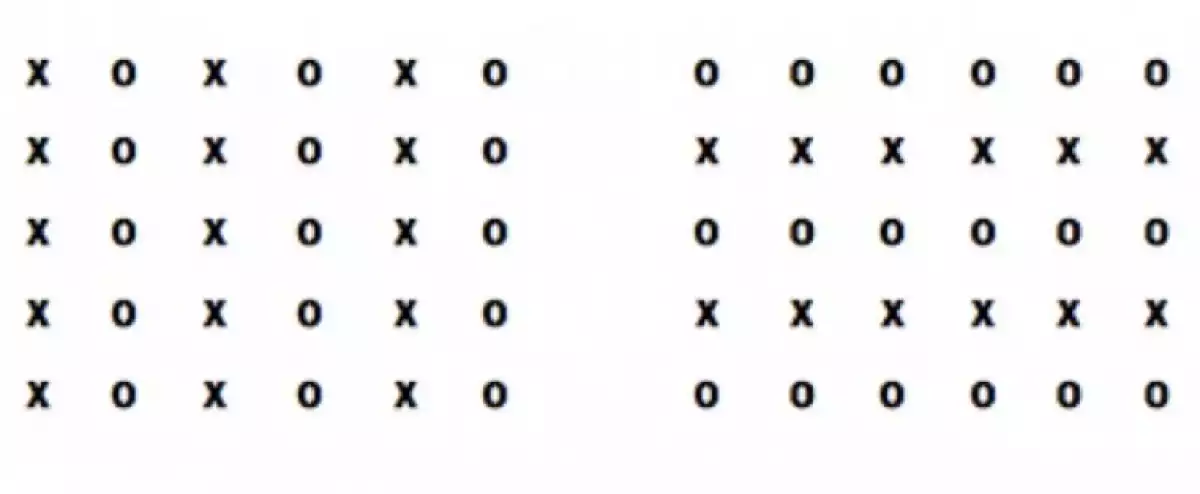

The law of similarity suggests that our perception classifies information depending on how similar it is to the other stimuli that we observe. This happens since we tend to look for homogeneity, so, if information presents itself frequently, we'll capture it before anything else that appears sparsely.

For example, an image presents itself with two blocks of figures. In the first block, there are five rows with this pattern: "x o x o x o," one on top of the other. The second block contains a row of six "o's" and then a row of six "x's," until you reach five columns.

Although the description could be the one that we just stated, in reality, when you ask people to put the objects into groups, they describe the first block as "columns" (because of the similarity of the x's) and the second block as "rows" for the same reason.

5. Law of pragnanz

The law of pragnanz, also known as the law of good figure, is the tendency to organize external phenomena into simple categories. For example, upon observing a soap bubble, we'll create a mental picture of its circular shape, texture, size, etcetera.

We do this with such ease that this information sticks in our minds and we'll be able to categorize similar shapes with the same classification later on. This last point leads to another one of Gestalt's principles, known as the law of experience (in the future we'll have access to images that seem familiar to us).

The law of pragnanz refers to 'good Gestalt' meaning, 'good shape': the kind that lasts in the mind of the observer, and in most cases has closure (favoring circumferences in this case). In other words, when given a choice, we tend to choose simple round shapes.

6. Figure and ground relationship

The Gestalt principles that we described before were also summarized in a single law: the law of figure and ground relationship. The laws mentioned beforehand describe how perception shapes the notion of an object, without highlighting the external elements that help to differentiate one shape from another.

On the other hand, the law of figure and ground relationship insists that perception also occurs through variations in the stimulation caused by external elements. This means that the information can't be organized perceptually alone; the subject needs a certain amount of contrast in order to acquire knowledge from this data.

So, the 'ground' refers to the homogenizing element, while the 'figure' is the element that creates contrast with the homogenous image present in the background. Besides, figure and ground can switch places. An example of this are images that give you certain information, but when you turn them around, they reflect something totally different.

Related: Bloom's Taxonomy: Verbs, Synonyms And Levels

Gestalt therapy

In the mid 20th century, the Gestalt principles and theory were brought into psychotherapy, thanks to the work of the German doctor and psychoanalyst, Fritz Perls (1893-1970) who was residing in the United States at the time. Just like Gestalt psychology disagrees with the affirmation that what happens in the mental framework is just the result of external stimuli, this type of psychotherapy is also opposed to the idea that psychological processes are only generated via external influences.

So, Gestalt defends the idea that psychological principles occur as a result of internal mental activity, in the same way that the Gestalt principles explain that perception happens via a series of internal mechanisms. But, while Max Wertheimer and other founders of Gestalt psychology focused solely on cognitive perceptions, Fritz Perls and Gestalt therapy followers emphasized the fact that the theory of shape (the Gestalt theory) also occurs on the emotional and motivational planes.

Considering the fact that Gestalt psychology had already proven that human beings don't perceive objects as isolated entities, but instead organize them based on the relationship between them, Gestalt therapy insists that depending on how a person organizes things, different symptoms, discomfort, and personal development roadblocks can come up.

In other words, beyond the external elements that cause these symptoms, the individual is responsible for organizing or reorganizing on a mental and emotional level. By the same token, in this type of therapy, focusing on the 'here and now' is essential. In this sense, this therapy attempts to work with the person as a unified entity where mental and emotional elements create a feedback loop. On the same note, this person learns to be conscious of what they feel and do at each moment in time.

Related: Hypnosis: Reality Or Myth? Main Uses And Techniques

Is this a type of humanistic therapy?

Gestalt therapy is classified as a type of humanistic therapy, within the psychotherapeutic currents of the second half of the 20th century. This is the case since it attempts to lessen psychopathological symptoms and signs, in addition to working towards personal development and if possible, self-fulfillment.

Besides, it avoids using the terms 'patient' or 'ill person,' substituting these terms for ones like 'client,' emphasizing the commercial relationship where the person that seeks therapy is requesting a service that the therapist can provide them with.

On the other hand, some people think that this is more of an existential therapy or a combination between existential and humanistic approaches since the latter includes part of the concept of self-fulfillment focused on the meaning of life and individual relationships with the world.

- This article about "The Gestalt Psychology" was originally published in Spanish in Viviendo La Salud

References

Burga, R. (1981). Terapia Gestáltica. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 13(1): 85-96.

Martin, A. (2006). Manual práctico de psicoterapia gestalt. Desclée De Brouwer.

Oviedo, G. (2004). La definición del concepto de percepción en psicoterapia con base en la Teoría Gestalt. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 18: 89-96.